I have always been fascinated about the history of the Phoenicians and of the later Carthage Empire also. I guess it is a sad story of a great pioneering civilization unable to capitalize on their maritime expertise resulting in their political and military might ebbing away. This interesting little article makes some nice references, especially to the identification of the English maritime spirit with that of the Phoenicians.

Although their military and political influence ebbed away over the centuries, their religious beliefs flourished even under the Roman empire. This is a civilization that has captivated me from a young age and which i know little about. There doesn’t seem to be a great deal information around about this culture, which is a shame as they seemed to have been an empire built on partnership and reciprocal benifit to those who they came in contact with. Trading empire.

Not sure about the fact that they never visited England as they say that the Phoenicians brought the tin which covered King Solomons temple, though admittedly I do not know any evidence to support this.

Here is the article (from the Al-Ahram Weekly in Cairo):

In the Phoenicians tracks

The Institut du monde arabe’s current Phoenicians exhibition is a rare opportunity to revisit a little-understood Mediterranean civilisation, writes David Tresilian in Paris

Widely advertised and long awaited, La Méditerranée des Phénicians, an exhibition that opened at the Institut du monde arabe in Paris on 6 October, affords a rare glimpse of ancient Phoenician civilisation, which dominated Mediterranean commerce for a millennium.

From their origins in a handful of city states scattered along the coast of today’s Lebanon, the Phoenicians founded a network of trading stations and colonies across the Mediterranean, from the city-states of Tyre and Sidon in the east to settlements on the Atlantic coasts of Spain and Morocco in the west, posing as significant rivals of first the ancient Greeks and then the Romans as they did so.

However, despite the Phoenicians’ trading and maritime skills — they were the first people to operate across the Mediterranean as a whole, unifying it as one vast commercial space — their history and culture is little known. No Phoenician literary works have survived from antiquity, which means that comments made by ancient Greek and Roman authors remain major sources for Phoenician history. Even the name “Phoenician” is of Greek origin, meaning something like “red-skinned”, the Phoenicians referring to themselves by their cities of origin.

Aside from advances in commerce, navigation, and the opening up of the Mediterranean to trade and colonisation, the Phoenicians left other achievements behind them. One of the most important was the introduction of the alphabet to the ancient Greeks, subsequent alphabetical scripts being traceable back to a Phoenician progenitor. In the standard story, Cadmus, a Phoenician prince, was sent to rescue his sister Europa, who had been carried off by the god Zeus. Though Cadmus did not succeed in rescuing Europa, he introduced the Phoenician alphabet to the Greeks while attempting to do so.

Later Phoenician history runs parallel to that of Carthage, originally a Phoenician colony whose ruins are in present-day Tunisia, and this city too has had a considerable afterlife. Prominent Carthaginians include Hannibal, who led a force of elephants across the Alps to attack Rome in 218 BCE, and the Carthaginian queen Dido, who, in Virgil’s account in the Aeneid, fell in love with Aeneas, fleeing across the Mediterranean after the fall of Troy. Dido was abandoned when Aeneas left the sanctuary she had provided to become the first founder of Rome.

This later Phoenician-Carthaginian history was once well-known to generations of schoolchildren brought up on the history of the Roman republic and the Punic wars. Even today it has not been forgotten. Nevertheless, the present exhibition does not revisit it, choosing instead to focus on the high point of Phoenician history from, roughly, the early Iron Age (the late New Kingdom in ancient Egyptian terms) to Alexander the Great’s conquests of the Phoenician city-states in 333 BCE.

While this has the advantage of not muddling the achievements of the Phoenician residents of Tyre, Sidon, Byblos and other centres in the eastern Mediterranean with those of the later Carthaginians in the west, some visitors may feel that an opportunity to review some splendid historical material has been missed. This material is as much a part of the history of Tunisia as the original Phoenician cities are of Lebanon, and therefore it is also a part of the Institut du monde arabe’s mandate.

That said, while some may regret the decision to halt the exhibition well before Alexander’s conquest of the eastern Phoenician world and the later conflict between Carthage and Rome, few will have anything but praise for the splendid array of Phoenician artifacts the curators have been able to assemble in Paris.

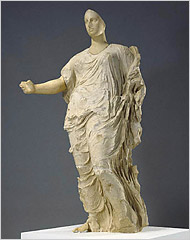

Lent by museums and institutions throughout the world, many of them in Lebanon, Tunisia and other countries having Phoenician sites, these include examples of Phoenician metalwork, ceramics, jewellery and funerary items. Highlights include a set of Egyptianising anthropomorphic sarcophaguses and uniquely Phoenician decorated tridacne shells, ostrich eggs and clay masks.

As curator Elisabeth Fontan notes in the exhibition catalogue, La Méditerranée des Phénicians aims to throw light on “traits that traditionally have been ascribed to the Phoenicians, as intrepid navigators, tough-minded merchants, inventors of the alphabet and craftsmen of genius, while at the same time indicating their presence from one end of the Mediterranean to the other.”

On entering the show, visitors are presented with a map of the ancient Mediterranean showing the extent of Phoenician territorial advances, followed by an account of their “rediscovery” in the 19th century by European archaeologists. Prominent in the first room is the “Cippe de Malte”, lent by the Louvre, which stands in the same relation to Phoenician archaeology as the Rosetta Stone does to ancient Egyptian. This low pillar, originally used to mark a tomb, bears a bilingual inscription in Greek and Phoenician, which allowed the later language to be deciphered at the end of the 18th century.

A Frenchman, the Abbé Barthélemy, was responsible for early advances in the study of the Phoenician language and for the establishment of its connections to other Semitic languages. However, it was another, later Frenchman, the 19th-century orientalist Ernest Renan, who perhaps did most to recall the Phoenicians to world attention. Sent by Napoleon III to investigate Phoenician sites in the eastern Mediterranean in 1860, Renan returned with an account of them that rivals the famous Description de l’Egypte produced by French savants half a century before.

The fruits of a century and a half of investigation since Renan’s time can be viewed in the rooms that follow. “Phoenician art,” Renan wrote, was above all an “art of imitation”, the Phoenicians having made the most of their position as a set of small, commercially minded city-states in a world of great empires. Borrowing designs and motifs from the ancient Egyptians, the Assyrians and the Greeks, the Phoenicians had a prodigious capacity to produce metalwork, jewellery, ceramics and other items that would appeal to the tastes of their rich neighbours.

Theirs was an art made to be bought and sold, with Phoenician goods being shipped across the Mediterranean in characteristic horse-prowed ships from entrepôts in the Levant and Cyprus. The exhibition includes many examples of Phoenician manufactured goods, including bronze or silver cups and bowls decorated with Egyptianising motifs such as scarabs and sphinxes, faience ceramics, glassware, and carved ivory plaques in Egyptian or Assyrian styles.

The Phoenicians were also famous in antiquity for their trade in raw materials, among them a kind of “Tyrian purple” dye made from seashells native to the Levantine coast that was highly prized by Roman emperors. The Phoenicians provided the Egyptian pharaohs with timber, and the exhibition includes a set of clay tablets, found at the Egyptian site of Tel el-Amarna, detailing relations between the Phoenician city-states and their powerful Egyptian neighbour.

Commercial success, however, does not seem to have endeared the Phoenicians to their neighbours, and ancient authors paint an unflattering portrait of them. Homer’s portrayal of a slippery Phoenician merchant in The Odyssey seems to have relied upon a well-known caricature, for example, and Cicero, equally biased, blamed the Phoenicians for undermining Greek civilisation by introducing a taste for luxury goods into it at the expense of solid public virtues.

Aside from the Phoenician goods on display, the exhibition also presents finds made in Phoenician tombs and funerary complexes, or tophets, excavated across the Mediterranean. These include Egyptian-style sarcophaguses bearing carved human heads found at sites across the Levant and dating from the 5th century BCE and various clay jars, figurines and masks. Phoenician religion seems to have been a highly complicated affair, with each city having its own religious pantheon. The exhibition includes bronze statuettes of various Phoenician gods, often with bizarre and unfamiliar names, many of which show clear Egyptian influence.

Writing on Carthage in the exhibition catalogue, M’Hamed Hassine Fantar of El-Manar University in Tunis says that the Phoenicians and Carthaginians probably did not sacrifice children to their gods Baal and Moloch, contrary to the account given by Roman historians and many centuries later by Flaubert in his Carthaginian novel Salammbô.

The exhibition ends with a film presentation of the Phoenician afterlife in European art and literature, focusing on various famous episodes. These include the carrying off of Europa by Zeus, taken as a subject by generations of artists, and the imaginative uses made of Carthage by many European writers. There are clips from a film version of Salammbô directed in 1925 in monumental Cecil B. de Mille fashion by Pierre Morodon, as well as references to the different uses made of the tragedy of Dido.

While some 19th-century French writers saw industrial and commercial England as the inheritor of the Phoenician spirit, as opposed to France, guardian of Latin culture, certain English artists were happy to assume a Phoenician inheritance. Lord Leighton, for example, one of Victorian London’s most successful painters, produced a set of historical pictures one of which shows the arrival of Phoenician traders off the coast of south-west England in antiquity.

This episode, which almost certainly never occurred, presents the English as the heirs of Phoenician commercial and maritime virtues in a further unlikely transformation of this people’s continuing legacy.

La Méditerranée des Phénicians, de Tyr à Carthage, Institut du monde arabe, Paris, until 20 April 2008.

Getty Museum knowingly bought archaeological treasures stolen from Italy, investigation claims

Getty Museum knowingly bought archaeological treasures stolen from Italy, investigation claims

Recent Comments